Is MQA Dead on Arrival?

The truth is that we may eventually add MQA to the list of audio formats that have come and gone. This list includes HDCD, DVDA, and DSD. All three of these claimed to deliver some sort of sonic improvement, but all three have suffered from a lack of content. HDCD and the DVDA are dead while DSD may be on its death bed. All three were supported by hardware but have died due to a lack of recordings in these formats. It should be noted that the DVDA did bring us high resolution audio formats and these have survived while the DVDA itself has died. Two dead, one dying ... is MQA next?

Unproven Claims

It is curious that most of the claimed sonic advantages of these formats have never been proven. There are plenty of anecdotal accounts of miraculous improvements in the sound, but there is no hard evidence that people could tell the difference. If the differences are real, they are so small that they can only be resolved by the very best playback systems. Consequently, to the average music lover, the letters all blend together into some sort of meaningless alphabet soup: HDCDDVDADSDMQA...

A Look Inside the MQA Chain

To those of us who are interested in the best possible musical playback, the small details are important. The promise of "improved sound" always catches our attention.

But, at the present time, I remain skeptical of the sonic advantages of MQA and even more skeptical of its commercial viability. There is no question that MQA degrades the quality of the audio for users who do not have an MQA decoder. The compatible portion of the MQA signal is equivalent to about 13 to 15 bits at a sample rate of 44.1 kHz or 48 kHz. The loss of resolution is due to down sampling, dither noise, and pseudo-random noise from the high-frequency compression channel which occupies the lower 8 to 11 bits. When fully decoded, the resolution of MQA is limited to 17 bits at 96 kHz. Miska has shown that an MQA file actually occupies more space than a lossless 96 kHz 18-bit PCM file! Why settle for 17 bits when you can have an 18-bit file in a smaller package? MQA may be promising a sonic benefit and file-size benefit that it cannot deliver!

MQA Block Diagram

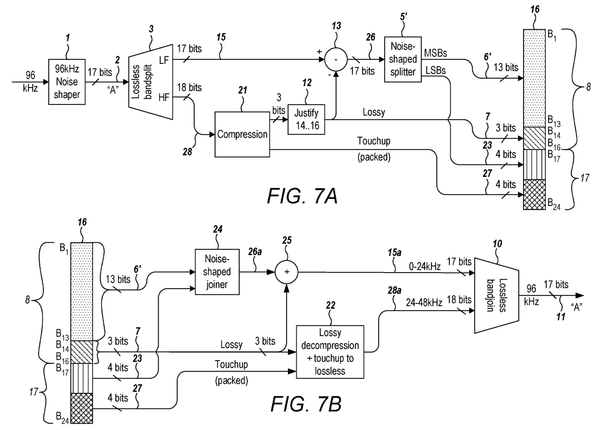

The following block diagram from one of the MQA patent applications shows the MQA system without the additional adaptive filters. The adaptive filters are covered by a separate patent.

The MQA encoder shown in Fig. 7A accepts a 96 kHz 24-bit input. This 24-bit input is immediately reduced to 17 bits using noise shaped dither (this is a lossy dithered quantization process that adds some noise above 20 kHz). The remaining 17 bits are split into high and low-frequency channels. The split signal is transmitted through a lossy compression system that is augmented by a compressed touch-up channel. If the touch-up channel does not overload, the 17-bit transmission is lossless if decoded as shown in Fig. 7B. But, if the touch-up channel reaches its maximum capability, the system begins to be a lossy 17-bit system. After decoding, a lossless or nearly lossless version of the 17 bit signal is recovered.

MQA is NOT Lossless

Note that the original 24-bit signal is never recovered. MQA does not losslessly preserve the original 24-bit signal. For this reason MQA is not truly a lossless system. At best, the MQA system losslessly conveys 17-bits at 96 kHz. Unfortunately this very complicated process is less efficient than lossless FLAC compression of the 17-bit file. It is also only slightly smaller than a FLAC version of the original 24-bit signal. MQA does not make it easier to stream 96 kHz files. With a 96 kHz 18-bit input, FLAC compressed MQA requires higher data rates than FLAC compressed PCM while delivering lower quality than 18-bit losslessly compressed PCM. MQA also requires special mastering and special playback hardware. Conventional FLAC compression requires neither.

Adaptive Filters

MQA also has an adaptive filter feature that is intended to shorten the rise time of short transients. Benchmark generally avoids these types of filters because we believe they do more damage than good. This is especially true as the sample rate increases.

Any attempts at "time-domain optimization" of the energy envelope will produce aliasing. This aliasing causes timing errors in the onset of transient events. With "time-domain optimization", transients tend to get reproduced in synchronization with the digital samples. The "optimized" digital system no longer has a continuous time response. The optimization removes inaudible ultrasonic pre-ring and creates an artifact that resembles jitter. Benchmark believes that this is a poor trade-off at 44.1 kHz sample rates and a complete mistake for higher sample rates. Again, we prefer the option of 96 kHz 18-bit audio or 96 kHz 24-bit audio to MQA-encoded audio.

Aliasing Artifacts

With MQA's adaptive filtering, transients are subjected to a distortion mechanism known as aliasing. This aliasing causes tonal shifts of high-frequency content and it causes small errors in the timing of fast transients. The MQA AES paper argues that the benefits of adaptive filtering outweigh the damage caused by the aliasing. The AES paper offers no proof that the adaptive filtering is solving an audible problem. It does however argue that the aliasing and timing errors, created by the adaptive filters, are nearly inaudible.

The primary benefit of MQA is the reduction in bit rate provided by the compression system. Again, this same or better reduction can be achieved with a conventional, non-aliasing downsampler and lossless compression. 192 kHz 24-bit material can be downsampled to 96 kHz and then compressed using FLAC lossless compression. The conventional FLAC compression yields a slightly smaller file with slightly better fidelity.

Due to the adaptive filters, the high frequency content that is reproduced at the end of the MQA chain is not the same as what was present in the original high sample rate files. If you ask me, I would rather listen to the original high-resolution content than a processed "enhanced" version.

The bottom line is that MQA is not necessary for streaming high-resolution files. If streaming services are not willing to stream lossless 192 kHz files, lossless 96 kHz files offer a better alternative than MQA. There is no proof that anyone can tell the difference between 192 kHz and 96 kHz sample rates.

MQA Applied to Standard Resolution Masters

What about CD recordings? Does MQA improve the sound of a 44.1 kHz CD recording after it has been made? The MQA people claim that it does. Beware, as any processing that changes the sound can work in either direction. It may make one recording sound better while doing damage to another. Currently there are anecdotal claims that MQA sounds different, but this has not yet been proven. Are there differences and if so, are the differences improvements? Time may tell, or MQA may go the way of HDCD before we know the answer.

MQA Compatibility Issues

MQA requires a lossless transmission system from the file source to the final D/A converter. Benign DSP processes such as a digital volume control (used in moderation) immediately defeat the MQA decoding. The same is true for digital crossovers, digital EQ, and room correction. The MQA stream will be corrupted if any of these common processes are encountered. These common forms of digital processing will shut down the MQA decoder and revert the system to a 44.1 or 48 kHz sample rate and an effective bit depth of 13 to 15 bits.

Additional Reading:

"MEASUREMENTS: MQA (Master Quality Authenticated) Observations and The Big Picture..." - archimago.blogspot.com

"MEASUREMENTS / IMPRESSIONS: Meridian Explorer2 Analogue Output - 24/192 PCM vs. Decoded MQA." - archimago.blogspot.com

"MQA: FINAL "Final" comments... Simply put, why I don't like MQA." - archimago.blogspot.com

"Some analysis and comparison of MQA encoded FLAC vs normal optimized hires FLAC" - Miska, computeraudiophile.com

Patent Application:

"Doubly Compatible Lossless Audio Bandwidth Extension" - Meridian Audio Limited, Dec 6, 2013

Patent Documents:

"Doubly Compatible Lossless Audio Bandwidth Extension" - WIPO Patentscope

Note: Block diagram and references added 6/29/2016. This application note was revised 6/29/2016 to reflect additional information compiled from the references shown above.