Buy one component and save 10% on up to 2 cables. Buy 2 components and get 4 free cables. Free shipping on USA orders over $700.

Buy one component and save 10% on up to 2 cables. Buy 2 components and get 4 free cables. Free shipping on USA orders over $700.

Audio That Goes to 11

by John Siau April 10, 2014

It's on your iPhone, your Android and your computer. It's even on those CDs you put on a shelf somewhere. Audio that goes to 11.

If 10 is the clip point of digital audio, you actually have digital recordings that go to 11. Nigel Tufnel of Spinal Tap was on to something in 1984 when he explained that his Marshal amps "go to 11". If you have never seen "This is Spinal Tap" I suggest watching this short clip before reading on. Nigel's brilliant discussion sets the stage for this application note.

But, it's not just Spinal Tap recordings that "go to 11"; every recording you own may also "go to 11"! How is this possible? If 10 is the clip point of digital audio, how can there possibly be an 11? And, if we use Nigel's logic; if 10 is good, why isn't 11 better?

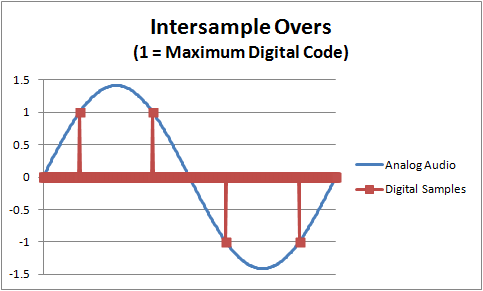

Getting to 11

As strange as it sounds, audio that "goes to 11" is hidden in between digital samples. This is especially true when the recorded samples just reach "10". Digital systems take a snapshot of the audio signal thousands of times per second. These snapshots or "samples" represent the audio signal at an instant in time. In between successive samples, the audio is always changing. Digital sampling systems often miss short audio peaks which occur between these samples. These peaks often "go to 11", but are entirely missed by the sampling system.

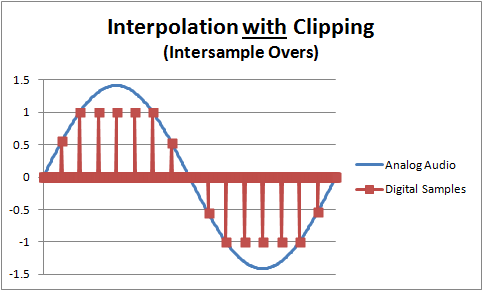

Nevertheless, the short peaks between samples are not lost! These peaks that "go to 11" can be reconstructed from the surrounding digital samples. The DAC (digital to analog converter) in an audio system is equipped with digital reconstruction filters that can recover these inter-sample peaks. These filters work wonderfully until the digital processing overflows. Peaks that hit "9" or "10" will not cause an overflow, but peaks that "go to 11" may cause an overflow.

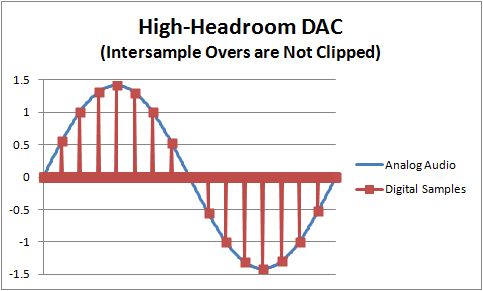

If you attempt to divide 1 by 0 on your calculator, the digital processing will overload and an error message will be displayed. Likewise, if the digital processing in your audio system overloads, bad things happen. Overflows that occur in digital reconstruction filters can produce a burst of distortion that persists for many samples. This distortion is non-musical and foreign to the natural sounds around us. These overloads often add an unnatural harshness to the digital playback system. But this does not mean that digital audio is fundamentally flawed. Some DACs can reproduce signals that "go to 11" without clipping. Benchmark's DAC2 is one such device.

Benchmark's Audio Research

Benchmark scanned over 5000 CD tracks to determine the severity of the inter-sample peaks in commercially available music. We discovered that most tracks contained peaks that were 1 or 2 dB above a full-scale "10". A peak that is 1 dB above full scale is 1.1 times as high as a full scale sample. A +1 dB inter-sample over is audio that goes to exactly 11! Nigel was right!

But back to our survey of CD tracks: we discovered some tracks had peaks that were 3.1 dB higher than full scale. This is 1.4 times as high as a full scale "10", and is audio that goes to 14 on Nigel's scale. You may own some recordings that go to 14, and you most certainly own many recordings that "go to 11".

Another twist to this situation is that MP3 compression seems to increase the occurrence of peaks that exceed full scale. This can make MP3 files sound worse than they should.

Once these problems were identified, Benchmark was able to implement a solution. The DAC2 reduces the signal level of the digital signal by 3.5 dB before it enters the digital interpolation and reconstruction filters in the DAC. This gain reduction is made up by increasing the analog gain after the D/A converter chip. The result is a DAC that not only "goes to 11", it is a DAC that "goes to 15". A peak of +3.5 dB is 1.5 times full scale (or "15" on Nigel's scale).

The Benchmark DAC2 goes to 15! Nigel should be impressed.

Leave a comment

Comments will be approved before showing up.

Also in Audio Application Notes

How Loud is the Distortion from Your Power Amplifier?

by John Siau August 08, 2025

Would you put a Washing Machine in your Listening Room?

If the answer is no, you may be surprised to discover that the distortion produced by your power amplifier may be louder than the noise produced by a major appliance.

Don't believe me? Take a look at Stereophile's test reports:

We selected 7 power amplifiers from Stereophile's top list of recommended amplifiers.

We took Stereophile's "THD+N vs. Power" plots for each, and replotted the data in a format that shows the loudness of the THD+N at the listening position.

The results are shocking!

Amplifier THD+N is louder than expected!

The distortion from your amplifier may be louder than a washing machine on the spin cycle, or it may be totally silent. How does yours perform? The answer is hidden in Stereophile's THD+N plots.

This application note reveals the hidden truth:

"The Distortion from your Power Amplifier may be Louder than a Washing Machine!"

I know, it sounds crazy, but this is what the measurements show!

Interpolator Overload Distortion

by John Siau November 20, 2024

Most digital playback devices include digital interpolators. These interpolators increase the sample rate of the incoming audio to improve the performance of the playback system. Interpolators are essential in oversampled sigma-delta D/A converters, and in sample rate converters. In general, interpolators have vastly improved the performance of audio D/A converters by eliminating the need for analog brick wall filters. Nevertheless, digital interpolators have brick wall digital filters that can produce unique distortion signatures when they are overloaded.

10% Distortion

An interpolator that performs wonderfully when tested with standard test tones, may overload severely when playing the inter-sample musical peaks that are captured on a typical CD. In our tests, we observed THD+N levels exceeding 10% while interpolator overloads were occurring. The highest levels were produced by devices that included ASRC sample rate converters.

Audiophile Snake Oil

by John Siau April 05, 2024

The Audiophile Wild West

Audiophiles live in the wild west. $495 will buy an "audiophile fuse" to replace the $1 generic fuse that came in your audio amplifier. $10,000 will buy a set of "audiophile speaker cables" to replace the $20 wires you purchased at the local hardware store. We are told that these $10,000 cables can be improved if we add a set of $300 "cable elevators" to dampen vibrations. You didn't even know that you needed elevators! And let's not forget to budget at least $200 for each of the "isolation platforms" we will need under our electronic components. Furthermore, it seems that any so-called "audiophile power cord" that costs less than $100, does not belong in a high-end system. And, if cost is no object, there are premium versions of each that can be purchased by the most discerning customers. A top-of-the line power cord could run $5000. One magazine claims that "the majority of listeners were able to hear the difference between a $5 power cable and a $5,000 power cord". Can you hear the difference? If not, are you really an audiophile?